by Ed Dennison, Ed Dennison Archaeological Services Ltd

BRITISH MARBLE

In 1813, Rudolph Ackermann, Regency arbiter of good taste and publisher of The Repository of Arts, Literature and Fashion, exhorted his readers that it was their patriotic duty to express a strong preference for British marbles when considering the refurbishment of their apartments. He confidently stated that “our native marbles are deserving of public cultivation and many of them approach the perfection of antiques”. Some 38 years later, the Great Exhibition of October 1851 featured a large display of British marbles. Contemporary commentators praised the striking display, the rich variety of colours and forms of the stone, exhibited in both its rough and manufactured state; on no other occasion, they said, were so many examples of this beautiful stone brought together. All of this, and, as the Exhibition Jury Report proudly noted, British marbles could be obtained “at a much cheaper rate than those from abroad”.

In addition to the black marbles, during the 19th century, Britain produced a wide variety of other marbles, including the rosewood, the russet or birds-eye, the mottled, the light grey, and an especially sought-after red marble, resembling the rosso antico of Italy. They were used in all manner of ways, and the Great Exhibition displayed examples of fonts, tables, columns, slabs, vases, pedestals and chimney pieces, sometimes ornamented with etchings and engravings, with powdered white lead rubbed into the etched surface for greater effect.

Writing in Yorkshire Notes and Queries in 1885, John Salter was able to identify over 50 varieties of English and Irish marbles. Pre-eminent in the English trade was Derbyshire, the principal producer of black marbles – the Ashford marble works were established in c.1742. Black marble was also found in Westmorland, in Devon (principally around Plymouth), in Kilkenny and the Western Isles of Scotland. However, there was an important source much closer to home – Dentdale..

DENT MARBLE

Dent marble, like all of the other British marbles exhibited at the Great Exhibition, is not a “true” marble or metamorphic limestone, but an unaltered limestone; its beauty and ability to take a highly polished surface in its final form is, in large part, due to the high percentage of fossils that it contains – a particularly fine example of the Dent grey marble can be seen in the chancel of St Andrew’s Church.

The stone occurs in localised areas around Dent, Sedbergh and Garsdale. The Hardraw Scar and Simonstone limestones yield a good black colour when polished, whilst the grey marbles were found in the Undersett Limestone along the north side of Garsdale. It is generally held that the discovery that these limestones could be polished for ornamental use was made around 1760-1770, probably influenced by the earlier commercial exploitation of similar stones in Derbyshire. The most extensive quarrying sites were located on Highrake Moss and Greenside, but there were other smaller sites to the south and south-west of Gawthorp and at Deepdale Head, together with numerous shorter-lived quarries.

By the beginning of the 19th century, a strong local demand for Dent marble had developed. For example, in 1804, Webster and Airey, the principal firm of architects in Kendal, paid £9 10s for marble extracted in Garsdale, and a further £23 5s in 1808. In 1810, Webster also signed an agreement with the proprietors of the manor of Garsdale to take 1,000 feet of marble at 6d per cubic foot, and further significant purchases were made in 1813 and 1822. In these cases, the marble was moved out of the dale to be worked, as it was not until slightly later that a marble works became fully established in Dentdale.

QUARRYING SITES

In 2002 EDAS were commissioned by the Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority to undertake an assessment of later post-medieval marble and stone quarrying sites in the present-day parishes of Dent, Sedbergh and Gardsale. The first stage of work was a desk-based exercise, to identify quarries and stone processing works noted on the 1st edition Ordnance Survey maps and in other sources. Local information from members of the Sedbergh and District History Society and various other individuals, such as David Boulton and David Johnson, was also collated. Although it was acknowledged that many small or short-lived quarries will not have been recorded in the sources, a total of 49 sites were identified, which included 27 sandstone quarries and nine marble quarries. Twenty-two sites were subsequently visited, including all the previously noted marble quarries, apart from the Dale Head Quarry which had been destroyed in the 1870s by the construction of the Settle-Carlisle railway. Records in the form of a description, sketch survey and photographs were made.

It is unlikely that any of the identified sites date to before c.1760. The aforementioned Dale Head Quarry was operating from the 1780s and it is possible that Greenside Quarry on the north side of Garsdale may date from the late 18th century. Based on a limited amount of documentary evidence, it is known that the majority of the other marble quarries were active by the mid 19th century and that all had become disused by 1909.

Little evidence for working methods was seen at the quarries. Extraction was probably achieved using crowbars and other hand tools, and a few sites had what might have been dumps of semi-dressed stone, in addition to the more numerous flat-topped spoil heaps. However, there were no ruined structures or cranes, as survive at some of the sandstone quarries in the area. The former marble quarries at High Lathe Gill and Highrake Moss contained a few abandoned or discarded architectural or sculptural pieces suggesting that some carving and finishing took place on site, with completed pieces being taken away by horse or cart – this might therefore date activity to before c.1800 after which the Stone House marble works was established. None of the quarries had well constructed sledgeways, roadways or even rough tracks associated with them, and their isolated positions must have made the transport and movement of stone very difficult.

MARBLE WORKS

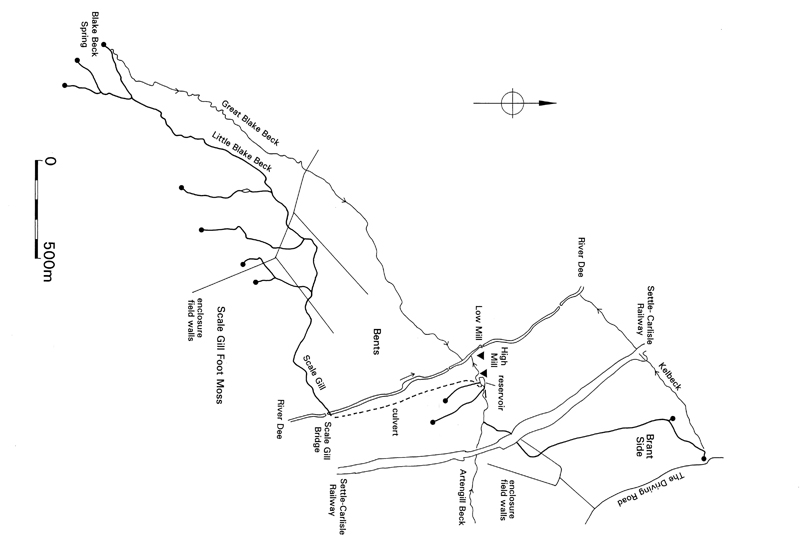

The only large scale marble works serving the Dentdale quarries was located at Stone House, at the confluence of the Artengill and Great Blake Becks and the River Dee, at the east end of Dentdale just below the Arten Gill viaduct. The siting of the works here was probably due to a combination of several different factors. Firstly, Stone House was situated within, although not central to, the area where the raw material was quarried, and it had relatively good transport links out of the dale. Secondly, suitable buildings were already present and may have become available at about the right time. Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, the site’s location at the confluence of two becks and the river made it easier to ensure the regular and constant supply of water which was needed to power the machinery; the owners of the works went to great lengths to manage and maintain the water supply.

WATER SUPPLY

A combination of field survey and documentary research, principally the 1859 Enclosure Award, has revealed three main sources for the water supply. The Enclosure Award notes that all the watercourses should be cleaned and kept in repair by the owners and occupiers of the marble works – their workmen should do no unnecessary damage to the fields through which they passed or reasonable compensation would be paid. The first water supply appears to have its origin at Widdale Great Tarn, some 3km north-east of Stone House. From here, a series of leats, springs and drains directed water into a c.1.5km long open drain on Brant Side to the north of Stone House. This drain then fed into the Artengill Beck just upstream of the works. The main drain on Brant Side survives as a prominent linear earthwork, some 6m wide overall and up to 3m deep, and an impressive culvert was built for the watercourse when the Settle to Carlisle railway was driven through the area in 1876.

The second main water supply starts on the high moors to the south-west of the works, where spring water was channelled into the Little Blake Beck on the west slopes of the valley, which ran down to the river Dee via Scale Gill. A number of bolts and other features projecting from the river bed here suggest a series of launders and sluices directing spring and river water into a large flat-topped stone culvert on the east bank, itself once fitted with an adjustable sluice. This culvert then ran underground north-west for some 800m before emerging on the east side of the Artengill Beck. From here, the water was taken along a leat built on the top of a stone revetted embankment, and was transferred into the marble works upper reservoir via an overhead launder supported on masonry pillars.

The third water supply brought spring water from Wold Fell to the south-east of the works in open leats and across the Arten Gill beck on a launder into a culvert visible by the side of a bridge. This culvert also received the Brant Side water via the beck. Further holding-down bolts, stone piers and other features in and around the beck give an indication of the route by which water was moved via timber launders from the beck to the works. A local elderly Dentdale resident recalled that in the 1920s there was still a forest of rotting launders, sluices and paddles in this part of the Arten Gill Beck. Water was directed into the works’ upper reservoir which powered a waterwheel in the High Mill, and was then passed to another reservoir and wheel associated with the Low Mill. From here, the water was returned to the river Dee via a tail race.

THE MILLS

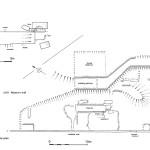

The marble works comprised two mills, High Mill and Low Mill, as well as ancillary workshops, a smithy, a showroom, offices etc. Although secondary publications generally state that the works were established in c.1800-1810, it is difficult to find primary documentary references to support this, and it might be that the works were in fact established or perhaps fully mechanised slightly later. The earliest reference appears to be “marble mills at Stonehouse, Dent, Yorkshire” in an 1829 Directory for Carlisle. In addition, in the few years before this, Dent marble was being taken to be worked at Preston Patrick near Milnthorpe, which implies that the Stone House works were not yet fully established.

The High Mill is also said to have originally been built as a corn mill but converted to a cotton spinning and carding mill in c.1780, and there are references to powered cotton spinning capacity still being available at Stone House in 1801. The High Mill was therefore probably converted to house marble cutting saws in the late 1820s. The Low Mill, on the other hand, was a new purpose-built structure.

In 1834 the Stone House works were described as being “.. a considerable manufactory for finishing and polishing marble, obtained here, on new and improved principles, conducted by the proprietor, Mr Paul Nixon”. Paul Nixon was born in Carlisle in 1768 and was a builder, surveyor, mason and architect who ran a thriving business with his partner and son-in-law William Denton – he established another marble works in Finkle Street in Carlisle in 1822. In the 1820s and 1830s the firm of Nixon and Denton built several churches in Carlisle and Whitehaven, numerous road and rail bridges in the north-west, and Shaddon Mill in Carlisle, and monuments signed by Nixon can be seen in many Cumbrian and North Yorkshire churches. As an architect, his principal work was the Academy of Fine Arts in Carlisle, built in 1823 and demolished in 1929. In a piece of excellent and thorough research, Enid Thompson has recently published a detailed history of the Nixon family, now available on the Dentdale website.

Paul Nixon was living in Stone House by 1824 and renting marble quarries in the area by March 1826 – as well as sourcing marble from these quarries, he also imported white Carrera marble from Italy. By 1841 Carr Nixon, Paul Nixon’s nephew, had taken over the management of the works, and he was followed by his widow Frances and her sister Anne Blackmore from 1863.

When the raw quarried stone arrived at the works, it was cut into requisite sized pieces using the water-powered cutting saws housed in the High Mill. To ensure a smooth face to the cut stone, the saws needed not only the constant application of water but also a very fine sand, obtained from tarns and pits on Whernside. After being sawn in the High Mill, the pieces of marble were taken down to the Low Mill, which housed the cutting, grinding and polishing machinery. A sale notice of 1837 noted that the High Mill contained three cast-metal saw frames, while the Low Mill housed a floating machine, single saws, polishing frames and polishing benches.

The works’ principal products during the 19th century were church or cemetery monuments and chimney pieces (fire surrounds), with an extensive commission for the latter being received for the waiting rooms of the Midland Railway. A late 19th century works catalogue includes sketches and photographs of 451 different designs for tombstones and memorials to suit all tastes and pockets, varying from small headstones to obelisks over 6m in height. The overall extent of the trade is difficult to estimate, but Arthur Raistrick has suggested that between 1842 and 1844 alone the works produced some 420 chimney pieces. Many were destined for local buyers, but large numbers were sent to warehousemen in Newcastle, Sunderland and Darlington, and others went abroad via London. The quarried stone was also used for more structural elements, for example the Artengill viaduct near Stone House and the Dent Head viaduct on the Settle-Carlisle railway are both built of rock-faced marble blocks.

Unfortunately, much of the High Mill was demolished in the 1920s, although the present house on the site forms a small part of the original structure, and some architectural features can be seen. The footings of the original c.9m long west gable of the mill are also visible in a wall bordering the beck, and the earthworks of the mill’s former reservoir as well as the remains of culverts and the wheelpit can be seen in the garden. Little also remains of the Low Mill, formerly located on the east side of the road running through the hamlet, although earthworks and the walls of the wheelpit and reservoir can be seen amongst wood and scrub. A late 19th/early 20th century photograph depicts the mill as a substantial two storey 10 bay structure – this mill had a 60ft diameter waterwheel, described as being newly installed in 1837.

Between the two mills was what was to become the works manager’s house, probably built in the 1800s, perhaps as a mill managers house, and between 1824 and 1841 owned and occupied by Paul Nixon. This was also where other investors, owners and later managers lived, such as Carr Nixon, as well as some of the masons, sawers and polishers employed in the works. In 1837 it was described as “good dwelling house with a large garden”, and low earthworks to the west of the house represent former flower beds and lawns, some edged with stone.

GROWTH AND DECLINE

Apart from making the obvious comment that the industry formed an important part of the economic and social life of the dale, it is difficult to estimate the exact number of people that were actually involved in the trade. The census data shows that Carr Nixon was employing 12 men at the works in 1851, as was Francis Nixon 20 years later in 1871 – many of these workers, described as masons, polishers or sawyers, were resident or lodging in houses in the village. Further afield, various trade directories of the early 19th century, and especially after c.1850, list numerous stone masons in Dentdale, many of whom were probably working marble and combining their trade with other employment. For example, in 1851, George Howson at Cow Dubb combined employment as a marble mason with that of an innkeeper, whilst in 1871, John Greenbank of Carlow Hill was a marble mason, foreman of the works and a Wesleyan lay preacher. Many others would also have been employed in ancillary activities, such as quarrying and transportation.

The trade in Dent marble was boosted by the construction of the Settle to Carlisle railway in the 1870s, and Francis Nixon secured some £1,300 compensation when the railway built the Dent Head viaduct over one of her quarries. However, any advantage was to some extent offset by the fact that the railway made it easier to import better quality Italian marbles. The trade was more seriously affected after c.1890 when the import tariff on Italian marble was removed. The writing had perhaps been on the wall as early as 1851, when a less patriotic visitor to the Great Exhibition noted of British marbles that “the material is somewhat brittle and rather expensive in working, at least as compared with the abundant and low priced marbles of the Continent”.

By 1887 the works were wholly owned by Blackmore and Company, and by 1891, with William Nixon as absentee manager, only four masons and polishers were living in the hamlet. Although the late 19th century work’s catalogue lists 451 designs (as noted above), many were of white Italian marble rather than Dent marble, which might imply that local sources were becoming scarce. It was previously noted that the Ordnance Survey maps suggest that all the marble quarries in the area were disused by 1909.

Marble working finally ceased on the site in 1907, and the 1909 Ordnance Survey map names the two mills as being disused. By the 1920s, the High Mill was in poor structural condition and was partly demolished. The Low Mill continued to be used as a workshop for mending bicycles, motorbikes and other small pieces of machinery, but in 1928, following bad flooding, it was demolished and the stone used to repair the adjacent road. However, large numbers of marble products remained on site for sometime afterwards, and hundreds of cut but unpolished chimney pieces were bought by the Hodgson family of Dent and polished off-site for re-sale. Indeed, former products can still be found today, not only in the churchyards, houses, pubs and railway stations of the area but also as cut but unpolished slabs such as one visible in the garden of the former High Mill.

Please note that the remains of the Stone House marble works lie on private land, and permission should be sought from the landowner(s) before entering their property.

Further information on this subject may be obtained from three EDAS reports for the Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority, available on-line by searching the Grey Literature for “dent marble” on the Archaeology Data Services website.

(Page created 30/04/14)